INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT with WKNO's Christopher Blank and Daily Memphian reporter Bill Dries.

CHRISTOPHER BLANK (WKNO): Fifty years ago this month, an attempt to make Memphis schools less segregated changed the landscape of education in this county and set a course for the highly segregated educational system we have today. Bill Dries, a reporter with the Daily Memphian, has written a six-part series about the fallout from court-ordered busing. The last chapter publishes tomorrow (Friday, Sept. 29). He joins me now. Good to have you, Bill.

BILL DRIES (Daily Memphian): Good to be here, Christopher.

BLANK: Your series starts by pointing out that in the early 1970s — and just two decades after Brown vs. Board of Education — local officials were still trying to figure out how, in a city where communities themselves were segregated, you could fix that social problem in our school system. And their first plan was a version of school choice — letting parents voluntarily move their kids to different schools. Why didn't that pan out?

DRIES: Well, the court basically concluded that that was a ruse; that if you tried to integrate a school by those means the excuse was going to be "well, that school doesn't have room for you there. So we can't let you do that." And it never resulted in any substantial integration.

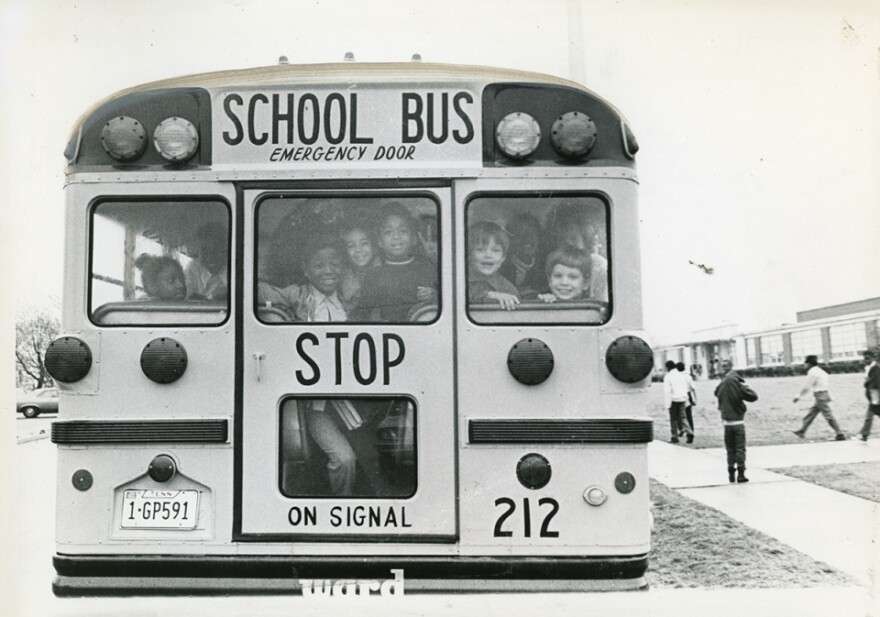

BLANK: So in 1973, they introduce busing — basically sending white kids to Black schools and vice versa. And this had some serious consequences. Can you talk about some of the problems from the outset?

DRIES: From the very outset, the city school system didn't own any buses. So they had to buy a new fleet of buses in the process. What they also faced were lingering questions about: is there any way to do this voluntarily?

BLANK: But there was also things like kids having to be at bus stops at 5:30 in the morning, you know, kids separated from their old friends, family members not being able to be active in their kids schools because of the distance, not being able to attend games and things like that.

DRIES: And you also had the arbitrariness of the boundaries. The school system, in drawing the boundaries, what you had were a lot of situations where kids on one side of the street were gonna stay at their neighborhood school and the kids on the other side of the street — the other side of a two-lane suburban road with a cul-de-sac, let's say — those kids were being bused. That's how close the boundaries were and trying to make the numbers work here.

BLANK: You were a student in one of these newly integrated schools, and I like that you include your experience in your reporting. What did this look like from a student's perspective?

DRIES: Looking back on it, teenagers even in the best of circumstances, are undergoing a lot of changes at about this age group in high school. So we just had to make it work on a daily basis.

BLANK: But you talk about there was tension in your school.

DRIES: Oh, sure.

BLANK: And that you talk about coming back from spring break to a lockdown because of some fights and protests.

DRIES: Yeah. No, the school had a full-blown riot. It was as ugly as you can probably imagine that it could be.

BLANK: Do you think incidents like these kind of validated some of those claims that this isn't gonna work — this level of integration is not going to work?

DRIES: My view on that — and it's solely my view — is that there were not only adults who felt validated, there were adults in the community who were rooting for this kind of violence to happen and for kids to get hurt. That's my opinion.

BLANK: The last part of your series, which comes out tomorrow, looks at how busing still affects our school system today. And here's the irony: Memphis schools are more segregated now than in the 1970s. And in retrospect, do you think things would be different today if busing had never happened here?

DRIES: The comments that are in this section are kind of all over the map on that. And there's a lot of speculation about whether this would have happened if there had been no dramatic change which busing was the epitome of. Marcus Pullman, who wrote the book that's a case study of this, called "Opportunity Lost," he put forward an idea that, well, maybe it would have worked if you had had one-way busing that involved exclusively sending Black students to white schools, but not white students to Black schools. That if that had gone for five years then maybe the stage would have been set for a more successful type of integration. And Pullman realizes that is a rather shocking scenario that some people would react to very badly, saying, "well, only the Black kids can integrate the schools and none of this is going to be on the white kids or the white families. You also have some folks who see the merger of public education in Shelby County that happened 10 years ago, 40 years after busing, that that was a second lost opportunity, so to speak here, to try to get this right by having everyone in the same school system.

BLANK: Daily Memphian reporter Bill Dries' six-part series on the consequences of court-ordered busing concludes tomorrow. Bill, thanks for joining us.