This story, a collaboration between WKNO-FM and the Institute for Public Service Reporting originally aired as three episodes on June 13-15, 2023. It was adapted from a series of student-written podcasts, available here.

This half-hour documentary version premiered as part of WKNO's Juneteenth commemoration on June 19, 2023.

PART 1

CHRISTOPHER BLANK: It sounds like a typical assignment for a seasoned journalist: find some interesting piece of Memphis history, maybe something that has never really been explored and then make a podcast about it.

That's exactly what Laura Faith Kebede intended back in January when she started teaching her first journalism class at the University of Memphis. She's with the Institute for Public Service Reporting.

Hi Laura good to see you.

LAURA KEBEDE: You too.

BLANK: So the podcast is finished.

KEBEDE: Yes, it was definitely a learning experience for everyone.

BLANK: Now, last year we worked together on a series for WKNO called "Civil Wrongs" and the concept is that some historical injustices still reverberate today. How did you come up with the theme for this second round?

KEBEDE: Well, you know, Memphis is kind of synonymous with civil rights, but most people think of it as it all happened in the 1960s. You think of segregation and Martin Luther King Jr. But very few people know about what we call the Memphis Massacre, which happened right after the Civil War.

BLANK: That's going way back.

KEBEDE: Yes, but in so many ways, we're still living the outcomes of this history.

BLANK: Well Laura, I just so happen to have some brand new podcast music by Andrew J. Crutcher who worked with us last time. I wonder: what if we did a little version of our own podcast right here?

KEBEDE: Let's do it.

BLANK: Okay here goes.

[Music]

I guess I'll do the intro... This is is "Civil Wrongs" an investigative series by WKNO and the Institute for Public Service Reporting. Here in Season 2, we investigate the Memphis Massacre and why it still matters today.

KEBEDE: Here at South Main Street and G.E. Patterson, there's history on every corner: Central Station, The Arcade—the oldest restaurant in the city, the famous dive bar Earnestine and Hazel's. All a block away from the Lorraine Motel and the balcony where Dr. King was killed.

Here comes the trolley...

If you close your eyes and tune out the cars and jukeboxes, it's still hard to imagine that this was once a site of mass carnage — buildings on fire, bodies in the streets.

In 1866, a year after the Civil War, there was a Union Army fort just down the street. It was made up mostly of black soldiers. Around it: a growing Community full of recently emancipated people. Let's think of it as one of Memphis's first black neighborhoods, with churches, schools, homes. So how does all this promise — this hopefulness — turn into a nightmare of murder, arson, theft, rape and police brutality?

My class is in room 202 in the University of Memphis's journalism building. I've got computers, a projector, a whiteboard and 13 undergraduate students. Greta Hullman is one of three from Germany.

GRETA HOLMAN: I was really looking for classes that would teach me about this country and its history.

KEBEDE: Then there were students like Cal Tuttle from Baltimore, here because the class he wanted was canceled.

CAL TUTTLE: This was the only option left.

KEBEDE: No offense, he adds. I also had some locals. Turner Schneider is among the majority who tell me a version of this:

TURNER SCHNIDER: I've lived in Memphis my whole life and I've never heard of the Memphis Massacre until this semester, so...

KEBEDE: So in a lot of ways, we really are starting from scratch.

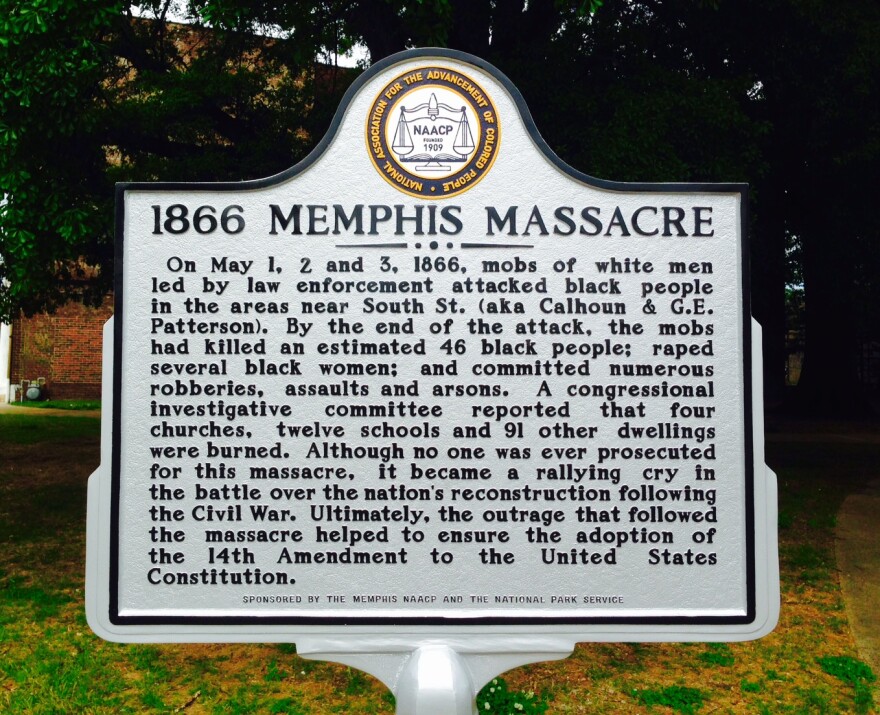

There are a few reasons the Memphis Massacre had been largely forgotten and certainly not taught in schools. For one, it had a different name in documents and even on a historic marker. It was called the "Memphis Race Riots of 1866," and if that suggests Black people destroying property to you, that was the intention.

BRYAN STEVENSON: We have tolerated narratives that are not factually accurate.

KEBEDE: That's Bryan Stevenson with the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama talking with WKNO back in 2016 on the 150th anniversary of the Massacre.

STEVENSON: Until we change the landscape with these markers and with these images and with a new iconography, we're going to be living in a space that is compromised by the absence of truth.

KEBEDE: He and others have been working to set records straight across the South. The truth of what happened got a boost by the first major book on the subject written in 2013 by the late University of Tennessee history professor Stephen V. Ash. He put the word "massacre" in the title.

So why emphasize Massacre?

On April 30th 1866, the Union Army was shutting down its operations here. Black soldiers were once again civilians. On this day a group of veterans got into a brief dispute with the members of the city's Irish police force. But without government backing, long-simmering tensions boiled over the next day.

Here's how Ash, speaking at a Rhodes College lecture, described what happened:

STEPHEN V. ASH: Mobs of white men armed with pistols and clubs formed up spontaneously Downtown, marched down to South Memphis and began shooting and beating Black people indiscriminately. Men, women and children: everyone they spotted on the street. Just shooting them down, or clubbing them.

Over the next 36 hours, other mobs repeatedly returned to the Black section of town and attacked Blacks on the streets, in their homes and set fires. Almost all the rioters were working-class Irishmen, including many policemen. The police were, in fact, basically the leaders, if you can call them that, of these mobs.

CHRISTOPHER BLANK: I remember, Laura, that the Tennessee Historical Commission would not put their stamp of approval on a marker here unless the words "race riot" were kept in the heading of it.

KEBEDE: Right? And this was the same time that they were trying to keep Memphis from taking down a statue of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. And five years later, there's still a lot of questions in education about whether you can even talk about these things at all in public schools.

BLANK: How so?

KEBEDE: Well, in 2021, state lawmakers passed a bill banning the teaching of certain divisive concepts, and one of those concepts is that racism is systemic. That it's baked into American history. Here's what governor Bill Lee said at the time:

TENNESSEE GOV. BILL LEE: What I'm most concerned about is that our education system reminds students that history is important, civics is important, American exceptionalism is important, and that political commentary is not important when teaching our children. That's what this bill will accomplish.

BLANK: Were you worried that a journalism class about the Memphis Massacre might be seen as one of those divisive concepts?

KEBEDE: Yes, and even more so 10 days into the semester.

[Sounds of news coverage surrounding the release of video and audio footage from the beating of Tyre Nichols.]

KEBEDE: I mean, here we are studying this event that happened 150 years ago, Memphis police exacting mob violence against Black people, and now it was happening again.

If that's not systemic, what do we call it?

And if it is systemic, how do we talk about it in schools or in a podcast for that matter?

PART 2

The historic marker for the Memphis Massacre now stands in a small park a few hundred yards away from the National Civil Rights Museum.

The State of Tennessee had nothing to do with it. It was the local NAACP and the National Park Service who settled on the final wording.

Even then, the short description can't tell the rest of the story: how the bloodshed on these streets heralded a century of abuses. Or how Dr. King's death, just around the corner, would continue the story.

For students in Laura Kebede's class, this small section of Memphis revealed a vast landscape of secret history.

DANIEL THOMA: Hey, Daniel Thoma here!

BLANK: Daniel is a foreign exchange student.

THOMA: What initially draw me to take this class was, first of all, the title of the class: social justice writing writing.

BLANK: Writing, specifically, about the Memphis Massacre. But the more he learned about this mob attack so shocking it pressured Congress to pass a new Constitutional amendment, the harder it was to understand why more people — especially his classmates who grew up here — did not know about it.

DANIEL: It's something that really rubs me off the wrong way, if something like horrible like that happens and people don't talk about it.

BLANK: Back home in Germany, Daniel says students begin those painful history lessons at an early age.

DANIEL: There is a culture of remembering and it's actually also put in law. Like denying that the Holocaust happened, for example, is a crime in Germany.

BLANK: While no one denies the Memphis Massacre happened, he thought some of the details were still relevant. Especially after Memphis police once again became the focus of a civil rights investigation.

That mob attack in 1866 had been led by police officers. Daniel learned this fact in January, just days before Memphis Police made a new mark on history.

[Audio from the police beating of Tyre Nichols]

The videos of Tyre Nichols' beating made Daniel Thoma wonder if America's whole cultural identity isn't lacking some important context.

DANIEL: I think what people need to learn is that it's not only the good parts that are part of that identity. Look at the bad parts, look at why they happened. Look at maybe the the structures that were in place. This is what you need to do, first of all in order to prevent those things from happening again. And also, it's what you need to do to have a complete picture of your own country's character and your own country's identity.

BLANK: As the students in Laura Kebede's class were learning, these incidents keep happening. Over the semester what ultimately emerged were patterns of historic injustices repeating themselves in real time.

KEBEDE: We were trying to make some modern connections. Like were there any living descendants of the victims or untold stories?

BLANK: What the class ultimately uncovered were patterns; historic injustices repeating themselves in real time.

KEBEDE: Whenever we talk about race and policing, many have focused on the race of the police officers, as if to make it about problematic individuals.

The police who led the Memphis Massacre were all Irish and they were considered an inferior race by white Southerners, which is kind of why local papers at the time kind of dismiss it as a "race riot." Irish people versus Black people.

So when Tyre Nichols was killed by Black police officers the conversation was forced to shift. What we end up seeing is the real historical pattern.

It's about the race of the victims and an abusive culture of policing in America.

That pattern has not changed.

REV. AL SHARPTON: We're not asking for nothing special. We're asking to be treated equal and to be treated fair.

BLANK: The Rev. Al Sharpton's eulogy for Tyre Nichols zeroed in on that pattern.

REV. SHARPTON: I can't speak for everybody in Memphis. I can't speak for everybody gathering. But for me, I believe that that man had been white, you wouldn't have beat him like that that night.

BLANK: Laura Kebede's students began making a list of parallels between past and present. It was frustrating, says Cal Tuttle, to learn that so many new rules or remedies have not worked.

TUTTLE: I just don't really understand how you can go through all this training and then you're gonna like sit there and look at me and tell me that like there was a threat?

BLANK: At age 17, Tuttle joined the U.S. Marine Corps. By 19, he was leading soldiers into dangerous situations.

TUTTLE: But I also knew that I wasn't supposed to be out there taking justice into my own hands.

BLANK: Tuttle took his concerns to a symposium on police accountability at the National Civil Rights Museum. It was Tyre Nichols' mother RowVaughn Wells who best reflected his own confusion.

ROWVAUGHN WELLS: I'm not understanding why this keeps happening.

BLANK: Since 2020, the Memphis Police Department, which is majority Black, has ended no-knock warrants, improved use-of-force reporting and now requires more cultural bias training for officers. As Wells noted, the technology used to catch criminals is also catching police misconduct.

WELLS: If that sky camera was not there, we wouldn't have known anything.

BLANK: Cal Tuttle likens the efforts to fix these problems through training and policy to the classes he was required to take in the military on the dangers of tobacco.

TUTTLE: I would take that class every year. And then I would immediately follow up that class by going outside and smoking a cigarette. Because that's just... that was the culture.

BLANK: The Memphis Massacre of 1866 and the more recent deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Tyre Nichols have another common thread. They all show the need for greater legal protections, and they all show how ineffective laws can be without cultural change.

Rhodes College history professor Tim Huebner says the summer after the Massacre Congress realized ending slavery was not enough. Black people needed strong Federal protections, even from government itself.

HUEBNER: As they said, quote, and this was I think Thaddeus Stevens who said 'the screams and the groans from Memphis' absolutely made it necessary for Congress to pass the 14th Amendment, and then of course for that eventually to be ratified by the states.

BLANK: The 14th Amendment gave newly emancipated people full citizenship and equal protection. It's still a cornerstone of American law — the basis of school desegregation, marriage equality and affirmative action.

Where else does it still come up? Police brutality cases

SHEILA JACKSON LEE: The whole issue is a climate. We are frozen in time.

BLANK: That's Texas Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee at a recent panel discussion in Memphis. Also frozen in time: her 2021 police accountability bill, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. It stalled in the Senate, even as the need for new measures keep getting added. After Memphis paramedics delayed medical care to Tyre Nichols, she tacked on a Duty to Intervene Act.

But even some voices of reform in law enforcement say the measures themselves are not enough.

CHERYL DORSEY: Police chiefs, if they really wanted to, they could fix all of this yesterday.

BLANK: Retired police Sergeant Cheryl Dorsey with the LAPD says police already have duties to intervene and keep data on problematic officers like the Scorpion unit that attacked Tyre Nichols.

DORSEY: If you don't do anything to deter the bad behavior, then the bad behavior continues.

So where does accountability start? And who leads the change on culture?

PART 3

CHRISTOPHER BLANK: In the parlance of detective work, this would be considered a cold case.

WAYNE DOWDY: We are off of Front Street in Downtown Memphis, near where Gayoso Street used to be.

BLANK: Memphis historian Wayne Dowdy is revisiting the scene of a crime.

DOWDY: So Front Street, for her, would be her main thoroughfare. This is where she would go to shop. This is where she would go probably take Front Street to whatever Church she attended...

BLANK: The victim was Francis Thompson. She lived nearby. On the night of the incident, seven white men entered her house — two of them wearing police badges. She and her roommate were sexually assaulted and robbed. No one was brought to trial.

The details of this crime exist because there was a public hearing about a month later.

And that hearing would change American history.

BLANK: As we continue our Civil Wrongs broadcast, a note to listeners that in the next few minutes we will be hearing from rape survivors — both historic and current.

They, too, are a legacy of the Memphis Massacre of 1866. In the wake of the attack, at least five incidents were reported by women who had the courage to testify.

For Reporter Laura Faith Kebede and her journalism class at the University of Memphis, voices from the past were the crux of this investigation. In fact, their echoes are still being heard.

LAURA FAITH KEBEDE: We were hoping we might get lucky. Maybe find a descendant of someone who survived. But at the end of the day we can only stand in front of the Gayoso House, an apartment building on Front Street, and imagine the grand hotel that was here in 1866.

This is where three members of Congress arrived from Washington D.C. in late May to examine witnesses.

The bodies of at least 46 Black men, women and children were found all over the streets of South Memphis. Countless others were robbed and beaten. 91 homes, four churches and 12 schools were set on fire.

The crimes are well-documented. More than 160 Witnesses showed up in person to testify.

University of Memphis history Professor Beverly Bond says the testimonies represent more than an act of Congress trying to figure out how the nation would move forward after the war. They are also, she says, acts of extreme courage.

BEVERLY BOND: When they go and they testify, it's kind of like saying, you know, maybe you're questioning my citizenship and our rights, but I have the right to my body and I have the right to property. You no longer have a right to control that.

KEBEDE: Witnesses had been threatened with retaliation by the same people who led the mob: Memphis police. Many fled the city.

But those who stayed would shape the future of Memphis.

BOND: The schools are rebuilt. You have the reconstruction of these churches. This violence happened, but you have many people — Black people — who say very simply, 'we're going to do it. We're going to build it again.'

KEBEDE: These witnesses were also building a new American narrative.

The students in my journalism class came of age in the era of #metoo. They read transcripts of 1866 and are shaken by how long survivors—especially Black women—have been fighting to be heard.

Rebecca Ann Bloom spoke out, difficult as it was to relive that night. Members of the mob broke into her house, removed her husband from the room and raped her.

For our podcast, we asked student actors to read dialog from the hearing.

CONGRESSMAN (ACTOR): Did they do anything to you?

REBECCA ANN BLOOM (ACTOR): They've done a very bad act.

CONGRESSMAN: Did they ravish you?

BLOOM: Yes, sir.

CONGRESSMAN: Did they violate your person against your consent?

BLOOM Yes, sir. I just had to give up to them. They said they would kill me if I did not. They put me on the bed and the other men were plundering the house while this man was... carrying on.

KEBEDE: Even then survivors were asked repeatedly why they didn't try harder to resist or escape. Did they protest enough?

This line of questioning, along with a failure to charge the assailants, is a legacy of the Memphis Massacre we're still living today.

Just ask Samantha Shell. She was 12-years-old when a man raped her in a park nearly 20 years ago.

SAMANTHA SHELL: "The ambulance and the police came. They took me to the rape crisis unit. They examined me. They kept me, then they released me from the hospital. That's the last time I heard about my rape kit. March the 17th, 2003.

KEBEDE: More than 12,000 rape kits were destroyed or untested by the Memphis Police Department in a scandal that came to light in 2013. Samantha Shell's was one of them.

SHELL: They failed us. And we reached out for help.

KEBEDE: Today there are still long delays in Memphis rape kit testing. Last year, after the abduction of Eliza Fletcher, it was discovered that her suspected killer might have been jailed months earlier had another woman's rape kit been tested.

SHELL: Memphis gotta hear our voice. You get what I'm saying? Because they never heard our voice. So I feel like, I'm gonna speak about it because I might help somebody else.

KEBEDE: The hearings that followed the Memphis Massacre confirmed the value of bearing witness, even if change is slow. The 1866 investigation pushed Congress to pass the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution. What it didn't do was stop white mobs from attacking Black communities.

Many massacres occurred over the next 60 years from Vicksburg, Mississippi to Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Each represents a failure to break a historical pattern, which is why those on the front lines of history education are worried.

BILL CAREY: Oh, hey everybody. It's History Bill.

Bill Carey is an author and reporter from Nashville. He's also the founder of Tennessee History for Kids and has a YouTube channel.

He and other educators have noticed a sidelining of certain topics.

CAREY: Tennessee may be the single worst state in the country in terms of teaching its own history. Most other states have like a year in eighth grade of their history. Tennessee only has a semester of Tennessee history in fifth grade. And now we're talking about moving that to third.

KEBEDE: My own students found that the Memphis Massacre is nowhere in the state's learning requirements. Not even an option, say, for kids in Memphis.

But conversations deemed not fit for classrooms are still being had in courtrooms.

Women whose rape kits went untested have filed a class action lawsuit. It's based on a history of Memphis Police neglect.

The family of Tyre Nichols is suing the City of Memphis for a half-billion dollars.

Attorney Ben Crump says that figure, too, comes from historic failures.

BEN CRUMP: It is our mission to make it financially unsustainable

for these police oppression units to unjustly kill black people in the future.

KEBEDE: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards Justice.

But it also doesn't bend itself. Each generation has a duty to intervene.

For many of my journalism students, the victims of the Memphis Massacre — those whose testimonies would never be heard —stand with us in spirit.

Their lives mattered.

The memory of this injustice is still relevant to the challenges we face here in Memphis.

And that is why it's so important to keep telling the story.