The promotion of religious freedom in America, a cause that not long ago had near unanimous support on Capitol Hill, has fallen victim to the culture wars.

A high point came in 1993, when Congress overwhelmingly passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, meant to overturn a Supreme Court decision that limited Americans' right to exercise their religion freely.

Those days are gone. The consensus surrounding religious freedom issues has been weakened by deep disputes over whether Americans should be free to exercise a religious objection to same sex marriage or artificial contraception and whether the U.S. Constitution mandates strict church-state separation.

For a long time in the country we kept it down to a dull roar. When that's no longer possible, it's a problem.

"It is more difficult to get a broad coalition on religious freedom efforts now," says Holly Hollman, general counsel at the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. "People have a bad taste in their mouth about what they think the other side thinks of religious freedom."

"It's a divisive issue," says Todd McFarland, associate general counsel at the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, a denomination historically known for its advocacy of religious freedom. "For a long time in the country we kept it down to a dull roar. When that's no longer possible, it's a problem."

The religious freedom question could arise again in the months ahead, as the U.S. Supreme Court considers whether to take new cases that involve the limits on Americans' religious rights.

In theory, the commitment to religious freedom is straightforward. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution bars Congress from making any law "respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

Most of the attention, especially in recent decades, has focused on the "free exercise" clause. An important case involved Adele Sherbet, a Seventh-day Adventist, who was fired for refusing to work on Saturdays and then denied unemployment benefits. In a 1963 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Sherbet's free exercise right had been violated.

In a 1990 decision, however, the Court significantly narrowed the Sherbet precedent, ruling against a Native American man, Alfred Smith, who was dismissed from his job because he had illegally ingested peyote as part of a religious ritual.

The Court's Smith ruling met with bipartisan outrage in the U.S. Congress and led to passage of the RFRA legislation. Among the sponsors was a first-term liberal Democrat from New York, Jerrold Nadler.

"Unless the Smith decision is overturned," Nadler argued on the House floor, "the fundamental right of all Americans to keep the Sabbath, observe religious dietary laws, to worship as their consciences dictate, will remain threatened." The bill passed the House unanimously and was approved in the Senate by a vote of 97-3.

Religious freedom politicized

In the years since, however, the religious freedom cause has been politicized, with conservatives claiming it for their purposes and liberals shying away from it for reasons of their own.

When liberals started pushing for expanded protections for the LGBT population, conservatives grew alarmed, arguing that practices such as same-sex weddings go against biblical teaching. They've argued that religious freedom should mean they can't be forced to accommodate something they don't believe in. Liberals portrayed that stance simply as discriminatory and argued it should be illegal.

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, made the issue a major theme of his campaign when he ran for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination.

"We're a nation that was founded on religious liberty," Cruz told an interviewer, "and the liberal intolerance we see trying to persecute those who as a matter of faith follow a biblical definition of marriage is fundamentally wrong."

When the conservative Heritage Foundation celebrated the 25th anniversary of the RFRA passage earlier this year, the organization's president, Kay Cole James, blamed "the left" for the erosion of the original consensus.

"I wish we could get that kind of bipartisan support today," she said. "The political left has actively worked to undercut our freedoms."

Religious freedom and discrimination

As conservatives focused the religious freedom debate narrowly around issues of sexuality and marriage, progressives doubled down on the promotion of LGBT rights. The Democrat-controlled House this month approved the "Equality Act," which would prohibit virtually all discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. One provision actually singles out the RFRA law, prohibiting its use as a defense against discrimination allegations.

Rep. Nadler, having originally been a RFRA backer, co-sponsored the new "Equality" legislation as chairman of the House Judiciary Committee.

"Religion is no excuse for discrimination in the public sphere, as we have long recognized when it comes to race, color, sex, and national origin," Nadler argued in a committee markup hearing, "and it should not be an excuse when it comes to sexual orientation or gender identity."

When the bill came up on the House floor, another co-sponsor, Democrat Bobby Scott of Virginia, explained why it may seem that progressives have turned cool on the Religious Freedom act.

"RFRA was originally enacted to serve as a safeguard for religious freedom," he said, "but recently it's been used a sword, to cut down the civil rights of too many individuals."

Some traditional advocates of religious freedom issues are dismayed by how the debate has evolved among both conservatives and liberals.

"When you [tell people] you work for the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, they want to know, 'What kind of religious liberty?'" says Hollman. She is evenhanded in her assessment of responsibility for the breakdown of bipartisan sentiment around the issue.

"It is unfortunate that some on the right will use religious freedom in order to advance a particular partisan issue," she says. "I think it is problematic on the left to cede arguments about religious freedom, to just say, 'Oh, people will use that now to advance an anti-LGBT perspective.' These are tough issues to work on, and religious freedom should not take the fall."

Fired for observing the Sabbath

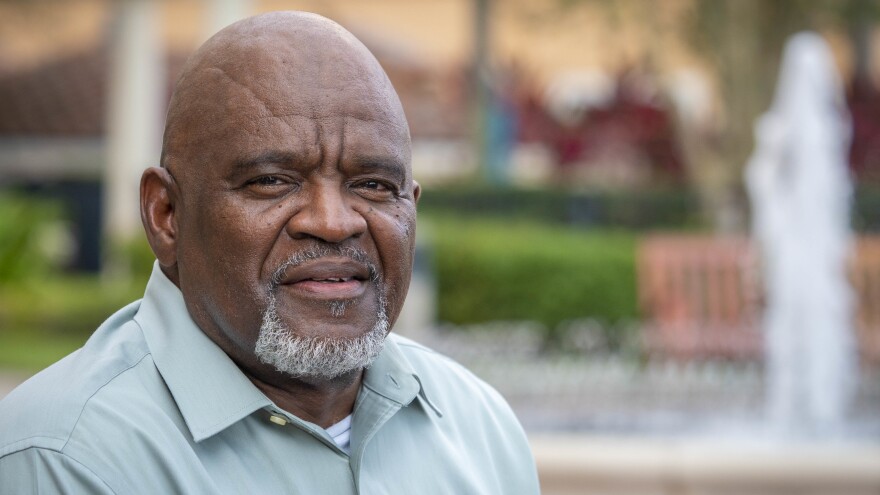

One current religious freedom case, in fact, is similar to those that led to the court fights of the last century. In 2005, a Seventh-day Adventist named Darrell Patterson interviewed for a trainer job at Walgreens in Orlando, Fla.

"I was completely up front with them that I observed the Sabbath and that the Sabbath was important to me," Patterson told NPR.

He got the job, and six years passed without a problem. But one Friday afternoon he was told to report to work the next morning.

"The Sabbath is a beautiful, beautiful day," Patterson said, explaining why working Saturdays is for him unthinkable. "If you were to come to my house on the Sabbath, you would find that our house is in order. There is a peaceful, serene atmosphere. My wife and my family spend time in prayer. We sing hymns together."

Patterson skipped work that Saturday. When he went in the following Monday, he was called into a supervisor's office and told that he was fired.

He sued.

In a statement to NPR, Walgreens says it is "committed to respecting and accommodating the religious practices of its employees" and "reasonably accommodated" Patterson's requested scheduling, but that doing more would have imposed "an undue hardship on our business." The Eleventh Circuit court ruled in favor of Walgreens, but Patterson is appealing.

The U.S. Supreme Court is considering whether to hear the case and revisit, yet again, the question of what religious freedom means.

McFarland from the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists is tracking the case closely. He expects Patterson to be broadly supported, but he also recognizes that the politics around religious freedom issues have shifted in recent decades.

"One of the most unfortunate things is that religious liberty has become the issue of one party," he says. "For Democrats, it's viewed as a divisive issue, especially in a primary context. [They say] 'how is this going to help me?' They used to feel that being on the right side of religious liberty was an important value, and they don't anymore."

Like the Baptist Joint Committee, however, the Seventh-day Adventists fault Republicans and Democrats alike for the politicization of religious freedom issues in recent years. The Adventists are bothered by the apparent reluctance of Republicans to embrace the "establishment' clause in the First Amendment, barring government from endorsing a religion. Conservatives have pushed for prayer and Bible readings in public schools and government funding for some religious institutions. Some have even suggested the United States be identified as a Christian nation.

"We have a strong interest in having a vigorous establishment clause," McFarland says. "That's something evangelicals and other conservative churches historically have not been as interested in. We are not trying to see the U.S. government impose any type of ideology. We have concerns about that. We have long believed that government and church need to stay in their separate spheres."

The Adventists' support for the establishment clause has allied them on various occasions with the American Civil Liberties Union, an unlikely partnership for other conservative Christian denominations.

The two parts of the freedom of religion provision in the First Amendment are sometimes seen as conflicting: Is the government in favor of religion or against it? But traditional American religious freedom advocates say the two clauses can also be read as complementary: The free exercise of religion is guaranteed only if it applies to all faiths. That can happen only if government does not take sides.

In Orlando, Fla., Darrell Patterson went back to school after being fired from Walgreens. He is now working as a mental health therapist. His campaign for the right to rest on the Sabbath, now possibly headed to the U.S. Supreme Court, no longer has to do with his own work situation.

"It's about other people that are going to come after me," Patterson says "that deserve to be able to practice their religious faith and conviction without putting their livelihoods in jeopardy."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.